The Collegiate Recovery Movement Is Gaining Strength

Butler Center for Research- September 2017

Overview

The college environment—where drinking and drug use might be perceived as defining the social setting—can pose significant challenges for students in recovery from addiction. At a time when a supportive peer network is so critical, students in recovery often feel a sense of disconnect from their peers. These challenges are compounded by other stressors, such as adjusting to new academic demands, freedom from parental supervision and financial pressures (Laudet, Harris, Kimball, Winters, & Moberg, 2014; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeyken, & Castillo, 1994; Wiebe, Cleveland, & Harris, 2010). Together, these factors can increase the risk for a return to substance use, commonly referred to as a relapse. In the face of such challenges, many young people in recovery find themselves choosing between recovery and staying in school. Dropping out of school might start to feel like a safer and more attractive alternative to risking relapse (Bell et al., 2009). Unfortunately, such a decision can also set a young person back in terms of establishing a fulfilling and prosperous career, which can serve as a long-term

recovery protector.

Collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) help students pursue their education and sustain their recovery simultaneously—a benefit to students, universities, parents and society alike. While the first CRPs began to emerge in the late 1970s and 1980s, the concept is gaining needed strength now, thanks in large part to the advocacy of those who have benefitted from such programs (Association of Recovery in Higher Education, 2017).

What Is "Recovery?"

Recovery is not just abstaining from all mind-altering substances (i.e., sobriety), but also includes embracing a positive view of wellness and personal growth (Betty Ford Institute, 2007; Laudet, 2007). Recovery is generally seen as a process, rather than a cure, and therefore requires ongoing support and effort to sustain (Harris, Baker, & Cleveland, 2010).

How Many College Students Are in Recovery?

The exact number of college students in recovery is not known. However, there are approximately 250,000 college students in the United States who have ever received treatment for alcohol or other drug use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive, 2014). It is plausible to assume many of these students are in recovery and need supportive resources to sustain their recovery. At the same time, 37 percent of college students engage in binge drinking and nearly 1 million U.S. college students meet standard clinical criteria for current alcohol or other drug dependence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive, 2014). These statistics illustrate the diversity of substance use experiences among college students.

Challenges and Opportunities of Recovery on a College Campus

Spending time in situations where alcohol and other drugs are being used—unfortunately, an all-too-common scenario on America's college campuses—and continuing to interact with friends who drink and use drugs are two reliable predictors of relapse, especially in early recovery. Conversely, having a strong support network of pro-recovery peers can serve as a critical counterweight to sustain recovery (Harris, Baker, Kimball, & Shumway, 2008; Harris et al., 2010). Parents and other caregivers can help their grown children maintain recovery in multiple ways [see http://continuingcare.drugfree.org; (The Treatment Research Institute and Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, 2016)]. One important way is by helping young people in recovery enroll in collegiate recovery programs so they don't have to choose between their education and their health.

What Can Colleges Do to Help?

Institutions of higher education are placing more and more emphasis on attending to the health needs and well-being of students. The notion that academic success is a function of both providing high-quality educational experiences and promoting physical and mental health is gaining traction. Students in recovery understand this connection well. Many colleges have financial constraints to prioritizing student health, much less being able to offer specific services to students in recovery. At many colleges, students in recovery are referred to off-campus resources. However, these external services, on their own, might not be adequate to support recovery because they are not tailored to address the unique set of stressors that college students face (Grahovac, Holleran Steiker, Sammons, & Millichamp, 2011). For this reason, expanding recovery support services in academic settings was named as a priority by the U.S. Department of Education and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (Dickard, Downs, & Cavanaugh, 2011) and also recognized in the Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs and Health (2016).

Collegiate Recovery Programs: Balancing Core Principles with Flexible Programming

In recent years, more colleges have started offering some form of support for collegiate recovery programs. Among the most well-known, established programs in the U.S. are the Collegiate Recovery Community at Texas Tech University and the StepUP program at Augsburg College in Minnesota. These two programs have served as models for the development of numerous other programs. Today, there are approximately 100 collegiate recovery programs across the United States (Association of Recovery in Higher Education, 2017).

Recent growth in collegiate recovery programs can be partially attributed to increased attention from state legislators. A recently passed bill in Maryland requires that schools in the University System of Maryland establish an on-campus CRP for students in recovery from alcohol and other drug use problems (General Assembly of Maryland, 2017). Similarly, New Jersey legislation passed in 2015 requires public universities to offer substance-free recovery housing if at least 25 percent of students live on campus (New Jersey State Senate, 2015).

Collegiate recovery programs can provide a supportive and safe space for students in recovery to further their education within an alternative social environment that supports their recovery, and helps them guard against the risky influences of other students' substance use. CRPs therefore enable students to further their education without jeopardizing their recovery. Programs tend to mature and become more comprehensive over time. At many campuses, the early phases of collegiate recovery programs have been student-led. However, staffing by addiction treatment or counseling specialists, as well as support from administrators in Student Affairs and health and wellness centers, can help develop a comprehensive CRP.

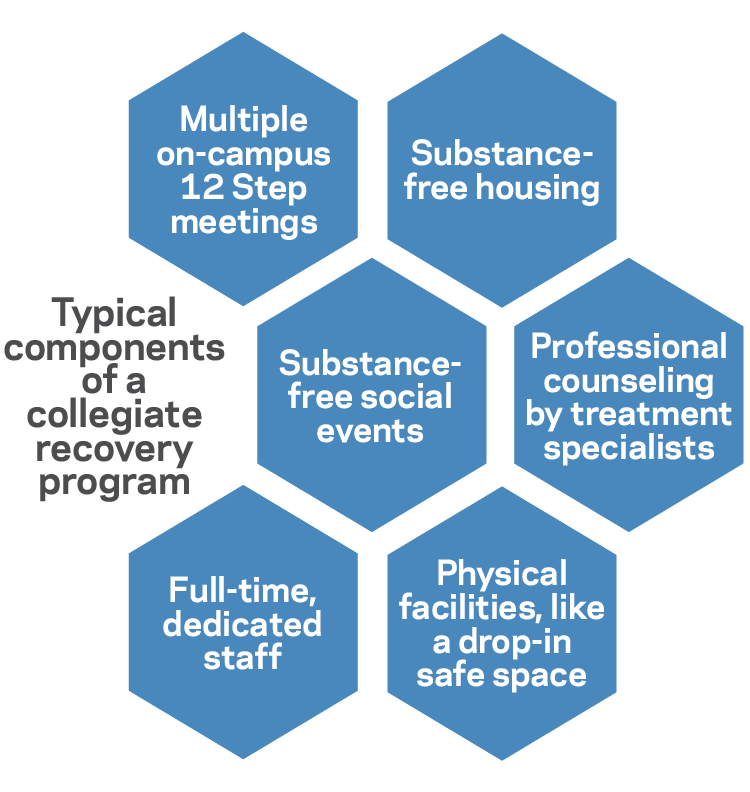

Generally, collegiate recovery programs offer access to recovery resources, such as counseling or substance-free housing, and have events geared toward students in recovery. The programmatic features of CRPs can vary depending on the size of the campus and the availability of resources. The common features of comprehensive collegiate recovery programs include substance-free housing and social events, dedicated space, on-campus Twelve Step support meetings, fulltime dedicated staff and professional counseling by addiction treatment specialists (Bugbee, Caldeira, Soong, Vincent, & Arria, 2016; Laudet et al., 2014). Some collegiate recovery programs have members sign a contract that requires sobriety, maintaining a minimum GPA and/or attending support meetings (Botzet, Winters, & Fahnhorst, 2007).

Offering support meetings on campus or substance-free housing are important components of collegiate recovery programs, but these alone might not be enough to constitute a CRP. Students in recovery who live in substance-free on-campus housing might also need additional peer support that comes from other campus-sponsored activities and programming. Indeed, college students can benefit most when they get involved in multiple recovery activities (Cleveland & Groenendyk, 2010). Collegiate recovery programs can encourage students to engage in several recovery support activities, and ensure that such activities are readily accessible within the campus community. Participation in such activities reinforces a shared commitment to recovery principles.

Additionally, at schools where juniors and seniors do not live on campus, relying solely on such substance-free housing as the mainstay of a collegiate recovery program could restrict opportunities to participate for older students.

There are many considerations for schools that are thinking about developing a collegiate recovery program, including deciding on entry requirements and on what is necessary to maintain membership. Given that student leadership is often transient as students graduate, succession planning must always be under development. Schools must also consider which administrators and staff on campus are most suited to provide administrative leadership. In addition, there are numerous logistical considerations, such as where on campus to offer substance-free housing or to place a substance-free recreation center or safe space.

The variety of possible components in a collegiate recovery programs offers flexibility for schools to develop a program that matches the needs of their students and the school. However, to be an effective CRP, schools must balance this flexibility with maintaining the principles of collegiate recovery, namely supporting students in sustaining recovery while also supporting personal growth and academic success.

How Do Students Benefit from Being Involved in a Collegiate Recovery Program?

The peer network provided by a collegiate recovery program is critical for students in recovery. Creating opportunities for students in recovery to socialize and develop a supportive social network can reduce the risk for relapse (Botzet et al., 2007; Cleveland & Groenendyk, 2010; Wiebe et al., 2010). In a survey of students from 29 Collegiate recovery programs across the United States, Laudet et al. (2016) found the peer support network was the most frequently cited reason for joining a CRP, mentioned by 56 percent of students.

Access to resources and treatment is also a key benefit of joining a collegiate recovery program. Laudet et al. (2016) found that nearly one-third of students joined the CRP because it offered a safe space on campus for recovery.

"Data from our cross-sectional, nationwide survey are encouraging," says Alexandre Laudet, director emeritus at the Center for the Study of Addictions and Recovery, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. "They show that CRPs offer students entering university a ready-made, same-age peer support network without which coping with a new, often 'abstinence-hostile' environment and with the pressures of college life would be highly stressful."

Collegiate recovery programs might also benefit the entire campus, not just the CRP members. First, a strong campus-based infrastructure of recovery support services might nudge some students toward recovery if they are already contemplating it. Moreover, students in recovery are likely to have a positive influence on reducing their peers' substance use, because their personal experiences represent authentic "cautionary tales" that can "dispel the allure of abusive drinking" (Misch, 2009). Collegiate recovery programs events can also be open to students who choose to not use alcohol or other drugs for reasons other than recovery. In this way, these programs not only serve students with a prior history of substance use problems but other students as well. Making these programs visible normalizes abstinence from alcohol or other drugs during college, and sends a message that substance use is not a necessary ingredient to having fun during college.

What's the Evidence to Support Establishing a Collegiate Recovery Program?

The goals of collegiate recovery programs are not simply to help students stay sober, but also to help them to stay in school and succeed academically. For this reason, CRPs are consistent with the fundamental mission of schools: to promote academic excellence and success. Laudet et al. (2016) found that 72 percent of CRP members said the CRP was "very important" to choosing their current institution, and 59 percent said that CRP participation was "extremely helpful" or "quite a bit" helpful. Importantly, about one-third reported they would not be in college currently if not for the recovery support on campus.

Preliminary research suggests that collegiate recovery programs contribute to both better academic outcomes and successful recovery. Data from the Collegiate Recovery Community at Texas Tech University suggest that its members have higher graduation rates and higher GPAs than the general student body (Harris et al., 2008; Laudet et al., 2014). Data collected from collegiate recovery programs nationwide show that students in CRPs have almost a 90% graduation rate compared with a 61% institution-wide graduation rate (Laudet, 2013). Furthermore, the relapse rate each semester is low, at approximately 4 percent to 8 percent. However, evaluations of CRPs, and even data collected from these programs, are very limited.

Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of collegiate recovery programs. CRPs should systematically collect data from their members and develop a plan for ongoing evaluation as a key component of the program.

Insights and Perspectives

William Moyers, Vice President of Public Affairs and Community Relations, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation

—"No longer is treatment a reason for a young person to stop pursuing their academic goals and dreams. Collegiate recovery programs give them an opportunity to gain traction in recovery, especially early on, even while returning to the stresses of academia and temptations of life on a college campus."

—"My own family has benefitted from the power of recovery on a college campus. It is a tremendous relief to any parent—me included—to know that getting a college degree and recovery go hand in hand for our children today."

Dr. Joseph Lee, Medical Director, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation Youth Continuum

—"The data so far suggest collegiate recovery programs are cost-effective and tremendously beneficial. We also know a great deal about the emotional and economic challenges that college students face. Outdated cultural norms associated with the college experience are antithetical to the fiercely competitive realities of a global marketplace, and they also create contradictory pressures for college administrators when it comes to substance use on campuses. The result of all this is a terrible irony--that collegiate recovery programs receive only a fraction of the support of Greek systems and other similar organizations."

—"Sobriety is ceasing compulsive and problematic substance use. Recovery is an ongoing commitment to address the risk factors and adversities that contributed to the development of the issue in the first place. Comparing substance use disorders to other chronic conditions, recovery would be parallel to the diet, exercise and emotional/spiritual self-care components of managing any disease."

—"Sobriety opens the door to the journey of recovery. The hopes and dreams of parents are realized when they see their children not only overcome adversity, but flourish on their path to young adulthood. In recovery, out of a young person's historical suffering come hope, connection and strength. Lessons of struggle inspire a grateful, humble and empathic perspective on life that many other young adults simply cannot grasp."

—"People in recovery are not only sober; they begin to align their lifestyles with the values they have always had within. As a result, recovering individuals start to become the people they were meant to be, the people that their loved ones always knew they were. Their relationships blossom, their dreams are realized and their hopes prosper. While hard to quantify academically, recovery has legitimate merit in the real world. In a health care culture obsessed with metrics and symptom management, recovery represents the best of holistic care. When you engage with young college students in recovery, it's impossible to not be awed by who they are and what they have to offer the world. Not much captures the humanistic spirit as well as recovery."

Nick Motu, Vice President, Hazelden Betty Ford Institute for Recovery Advocacy

—"One challenge facing college students returning to school after completing treatment or entering a school already in recovery is having access to a healthy, recovery-supportive social environment, one that provides safe haven from the 'Animal House' culture of substance use. Collegiate recovery programs offer recovering students these environments on college campuses."

Amy Boyd Austin, Board President, Association of Recovery in Higher Education, and Founding Director, University of Vermont's Catamount Recovery Program

—"Collegiate recovery is an essential part of the higher education landscape. It's integral to a continuum of care through its role in prevention, intervention and recovery support. Students in collegiate recovery programs have demonstrated higher student success through higher GPAs, retention rates and graduation rates. In the endeavor to shift college culture away from high-risk behaviors, highlighting efforts and success stories like students in recovery and other substance-free students is paramount to success."

Download the The Collegiate Recovery Movement Is Gaining Strength report.

References

- Association of Recovery in Higher Education. (2017). Collegiate recovery program members. Retrieved July 18, 2017, from https://collegiaterecovery.org/programs

- Bell, N. J., Kanitkar, K., Kerksiek, K. A., Watson, W., Das, A., Kostina-Ritchey, E., Russell, M. H., & Harris, K. (2009). "It has made college possible for me": Feedback on the impact of a university-based center for students in recovery. Journal of American College Health, 57(6),

650-658. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.6.650-658 - Betty Ford Institute. (2007). What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 221-228. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001

- Botzet, A. M., Winters, K., & Fahnhorst, T. (2007). An exploratory assessment of a college substance abuse recovery program: Augsburg College's StepUP Program. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 2(2-4), 257-270. doi:10.1080/15560350802081173

- Bugbee, B. A., Caldeira, K. M., Soong, A. M., Vincent, K. B., & Arria, A. M. (2016). Collegiate recovery programs: A win-win proposition for students and colleges. College Park, MD: Center on Young Adult Health and Development. Retrieved from

http://www.cls.umd.edu/docs/CRP.pdf - Cleveland, H. H., & Groenendyk, A. (2010). Daily lives of young adult members of a collegiate recovery community. In H. H.

- Cleveland, K. S. Harris & R. P. Wiebe (Eds.), Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence (77-95). New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Dickard, N., Downs, T., & Cavanaugh, D. (2011). Recovery/relapse prevention in educational settings for youth with substance use & co-occurring mental health disorders: 2010 consultative sessions report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Drug-Free

Schools. Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/Abstract.aspx?id=264490 - General Assembly of Maryland. (2017). Bill Number HB950: University System of Maryland - Constituent institutions - Alcohol and drug addiction recovery program.

- Grahovac, I., Holleran Steiker, L., Sammons, K., & Millichamp, K. (2011). University centers for students in recovery. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 11(3), 290-294. doi:10.1080/1533256X.2011.593990

- Harris, K. S., Baker, A. K., Kimball, T. G., & Shumway, S. T. (2008). Achieving systems-based sustained recovery: A comprehensive model for collegiate recovery communities. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 2(2-4), 220-237. doi:10.1080/15560350802080951

- Harris, K. S., Baker, A., & Cleveland, H. H. (2010). Collegiate recovery communities: What they are and how they support recovery. In H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris & R. P. Wiebe (Eds.), Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence. (9-22). New York, NY:

Springer Science+Business Media. - Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Winters, K., Moberg, D. P., & Kimball, T. (2013). Collegiate recovery programs: Results from the first national survey. Presented at the 4th Annual Conference on Collegiate Recovery. April 3-5, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX.

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., & Moberg, D. P. (2014). Collegiate recovery communities programs: What do we know and what do we need to know? Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(1), 84-100. doi:10.1080/153325 6x.2014.872015

- Laudet, A. B. (2007). What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 243-256. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.014

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., & Moberg, D. P. (2016). In college and in recovery: Reasons for joining a Collegiate Recovery Program. Journal of American College Health, 64(3), 238-246. doi:10.1080/07448481.2015.1117464

- Misch, D. A. (2009). On-campus programs to support college students in recovery. Journal of American College Health, 58(3), 279-280. doi:10.1080/07448480903295375

- New Jersey State Senate. (2015). Bill Number S2377: Directs certain four-year public institutions of higher education to establish substance abuse recovery housing program.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive. (2014). National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Series: NSDUH 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2017, from http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/SAMHDA/sda

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). SAMHSA's working definition of recovery: 10 guiding principles of recovery. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from

https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/PEP12-RECDEF/PEP12-RECDEF.pdf - Treatment Research Institute and Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. (2016). Continuing care: A parent's guide to your teen's recovery from substance abuse. Retrieved August 15, 2018, from http://continuingcare.drugfree.org

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved November

2016 from https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov - Wechsler, H., Davenport, A., Dowdall, G., Moeyken, B., & Castillo, S. (1994). Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272(21), 1672-1677.

doi:10.1001/jama.272.21.1672 - Wiebe, R. P., Cleveland, H. H., & Harris, K. S. (2010). The need for college recovery services. In H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris & R. P. Wiebe (Eds.), Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence. (1-8). New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.