Substance Use in the Workplace

Butler Center for Research - May 2015

Information About Workplace Prevention and Intervention Programs

Download the Substance Abuse in the Workplace Research Update.

Despite common misconceptions and negative stereotypes, approximately 79% of heavy drinkers 18 or older are employed.1 This presents a host of problems related to safety, productivity, and the impact of workplace substance use on coworkers.

Prevalence of Substance Use in the Workplace

Many researchers in recent years have attempted to better quantify the prevalence of substance use in the workplace and, perhaps more important, identify what factors significantly impact it. One model suggests that three dimensions significantly predict substance use in the workplace: (1) perceived availability of alcohol and/or illicit drugs, (2) the extent to which an individual's coworkers use or work while impaired by alcohol or drugs (descriptive norms), and (3) the level of approval by coworkers of workplace alcohol/drug use or working while impaired/ intoxicated (injunctive norms).2,3 Recent research with army soldiers uncovered that, regardless of actual norms, it is the perception of these descriptive and injunctive norms among peers and coworkers that are related to problem drinking behaviors.4

Using this three-dimensional model, researchers have been able to assess the overall prevalence of substance use in the workplace and identify a number of sub-populations that are at higher risk for workplace use. According to a 2012 study of 2,148 workers in the United States, 63.09% reported easy access to alcohol in the workplace (59.05% for illicit drugs), 23% reported high descriptive norms for alcohol use (12.65% for illicit drugs), and 7.03% reported high injunctive norms for alcohol use (3.55% for illicit drugs).5 Findings suggested that men, young people, and those with higher levels of education were at elevated risk for substance use in the workplace.5

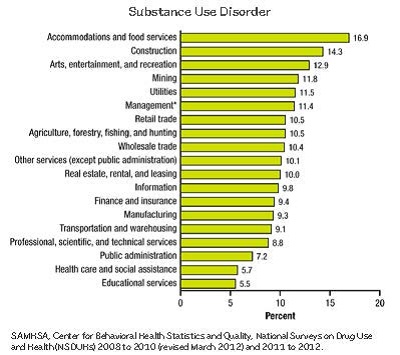

Rates for industry-specific drinking patterns are also important indicators of work environments and coworker norms. A recent 4-year national study on industry-specific patterns found that rates of problematic alcohol use were highest among those in the mining (17.5%) and construction (16.5%) industries.6 Workers in the food services industry had the highest reported rates of illicit drug use (19.1%) and substance use disorder (16.9%).6 Researchers have found that food service workers also report higher rates of coworker acceptance of workplace substance use.7 Similar social network effects have also been discovered in hotel workers, who also display elevated substance use and abuse behaviors.8

Impact on Employment Functioning

In addition to the general health and wellness problems associated with alcohol and drug abuse, there are a number of implications specific to employers. Alcohol and drug use have a negative impact on worker productivity, whether the use occurs off the job or on. A Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation survey of over 300 human resources professionals found that 67% believe substance use is one of the most serious issues they face among the workforce, with consequences related to absenteeism, reduced productivity, and a negative impact on their company's reputation.9 Workers with illicit drug and/or heavy alcohol use have higher rates of job turnover and absenteeism compared to those with no illicit drug or heavy alcohol use6 and are more likely to experience job-related injuries.10,11 In 1998 (the most recent year for which the numbers are available), it was estimated that the economic cost of substance use was more than $184 billion.12

Prevention and Intervention at Work

Since the enactment of the Drug-Free Federal Workplace Act in 1988, many employers have addressed the issue of employee substance use by requiring drug testing, especially in occupations that pose high risk of injury.11 Today, approximately 35 million drug tests are performed each year and have had a significant impact on reducing workplace injuries and mishaps.11 In addition, many employers have begun to offer services that provide support and assistance to employees with drug addiction or problem-drinking behaviors. Almost all (90%) Fortune 500 companies have Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) to address substance use problems. However, the numbers are far lower for smaller businesses (66% for businesses with 100-plus employees; 29% for businesses with 50–99 employees).13,14 This disparity could be the result of the high costs of implementing EAPs, although many employers have found that a successful EAP results in the added benefit of significant cost savings, while providing much needed support and assistance to their workers.11,13

Several different workplace-centric healthy lifestyle and social health campaigns—including the Power Tools curriculum geared toward construction workers, the Workscreen program for postal workers, and Team Awareness, a broad-use alcohol reduction program for use among small business workers and young restaurant workers—have shown promising findings.14,15,16

Web-based interventions have also resulted in positive outcomes for employees with unhealthy alcohol and drug use behaviors. An evaluation of the free intervention site CheckYourDrinking.net found that the site's intervention strategies significantly reduced consumption levels in high-risk drinkers, as compared to a control group.17 The U.S. Department of Defense studied the effects of a web-based intervention program for military called PATROL (Project for Alcohol Training, Research and Online Learning), which demonstrated success in reducing drinking behaviors in soldiers through three different group options.18 While not designed for use as a workplace-specific EAP, the online curriculum Moderation Management has also demonstrated success in reducing drinking and alcohol-related problems among users.19

Summary

Illicit drug and heavy alcohol use is problematic among the U.S. workforce and causes substantial consequences. Workplace prevention and intervention programs are effective in addressing substance use problems among employees. Treatment for alcohol and drug dependence is also effective in improving worker productivity and health. While few in number, cost-benefit studies have demonstrated an economic benefit to employers who implement programs and support treatment for employees.

The Hazelden Betty Ford Experience

To assist patients with the struggles related to substance use and work, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation offers programs that are geared toward specific professional groups at higher risk for drug and alcohol abuse and that deal with workplace stressors and other job-related concerns. Currently, we provide specialized residential and outpatient treatment programs for legal professionals and health care professionals. Additionally, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation commissions nationwide surveys of human resource professionals to better understand the pressures all companies face related to employee substance use.

Questions & Controversies

Can employers do anything to prevent substance abuse among employees?

Workplace prevention and intervention programs have demonstrated positive outcomes for improving workplace health and safety and have even shown promise at preventing substance abuse outside of the workplace.11 Materials are readily available to foster a drug-free work environment. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration offers a free Drug-Free Workplace Kit on their website. Organizations required to abide with the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 can find additional materials through the U.S. Department of Labor's website.

How to Use This Information

Employers: Implement effective prevention programs at your work site. Refer employees with substance use problems to assessment and treatment.

Human Resource Professionals: Encourage leaders at your company to implement prevention and intervention programs. Ask for training to identify and intervene with employees who may be experiencing substance use problems. Support treatment efforts among employees with alcohol and/or other drug dependence.

Coworkers: Many people who use alcohol or other drugs at work are under the impression that their coworkers approve of using alcohol or other drugs at work. Do your part to communicate that you support a drug-free workplace and do not encourage your peers to engage in drinking or other drug use behaviors.

References

1. Ensuring Solutions to Alcohol Problems. (2008, March). Workplace screening & brief intervention: What employers can and should do about excessive alcohol use. Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University Medical Center.

2. Ames, G. M., & Grube, J. W. (1999). Alcohol availability and workplace drinking: Mixed method analyses. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60, 383–393.

3. Hodgins, D. C., Williams, R., & Munro, G. (2009). Workplace responsibility, stress, alcohol availability, and norms as predictors of alcohol consumption-related problems. Substance Use and Misuse, 44(14), 2062–2069.

4. Neighbors, C., Walker, D., Rodriguez, L., Walton, T., Mbilinyi, L., Kaysen, D., & Roffman, R. (2014). Normative misperceptions of alcohol use among substance abusing Army personnel. Military Behavioral Health, 2(2), 203–209.

5. Frone, M. R. (2012). Workplace substance use climate: Prevalence and distribution in the U.S. workforce. Journal of Substance Use, 71(1), 72–83.

6. Bush, D. M., & Lipari, R. N. (2015, April 16). Substance use and substance use disorder by industry. The CBHSQ Report. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

7. Duke, M. R., Ames, G. M., Moore, R. S., & Cunradi, C. B. (2013). Divergent drinking patterns of restaurant workers: The influence of social networks and job position. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 28(1), 30–45.

8. Belhassen, Y. & Shani, A. (2012). Hotel workers’ substance use and abuse. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 1–11.

9. Hazelden Foundation (2007, July). Substance abuse and addiction among most serious workplace issues.

10. Spicer, R. S., Miller, T. R., & Smith, G. S. (2003). Worker substance use, workplace problems, and the risk of occupational injury: A matched case-control study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 570–578.

11. Zimbardi, G. (2005). Workplace substance use, the risk of occupational injury, and testing (Master’s thesis. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA).

12. Harwood, H. (2000). Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update methods, and data. (NIH Publication No. 984327). Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health.

13. Levy Merrick, E. S., Volpe-Vartanian, J., Horgan, C. M., & McCann, B. (2007). Revisiting employee assistance programs and substance use problems in the workplace: Key issues and a research agenda. Psychiatric Services, 58(10), 1262–1264.

14. Ames, G. M. & Bennett, J. B. (2011). Prevention interventions of alcohol problems in the workplace. Alcohol Research and Health, 34(2), 175–187.

15. Cook, R. F., Hersch, R. K., Back, A. S., & McPherson, T. L. (2004). The prevention of substance abuse among construction workers: A field test of a social-cognitive program. Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(3), 337–357.

16. Richmond, R., Kehoe, L., Heather, N., & Wodak, A. (2000). Evaluation of a workplace brief intervention for excessive alcohol consumption: The Workscreen project. Preventative Medicine, 30(1), 51–63.

17. Doumas, D. M. & Hannah, E. (2008). Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: A web-based normative feedback program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(3), 263–271.

18. Pemberton, M. (2007, November). PATROL: Pilot study: Findings and future plans. Session abstract no. 162656. 135th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Exposition. Washington, DC.

19. Hester, R. K., Delaney, H. D., Campbell, W., & Handmaker, N. (2009). A web application for moderation training: Initial results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37(3), 266–276.